|

For Writers Who Live Dangerously, Free Spirits, Overmen and Overwomen

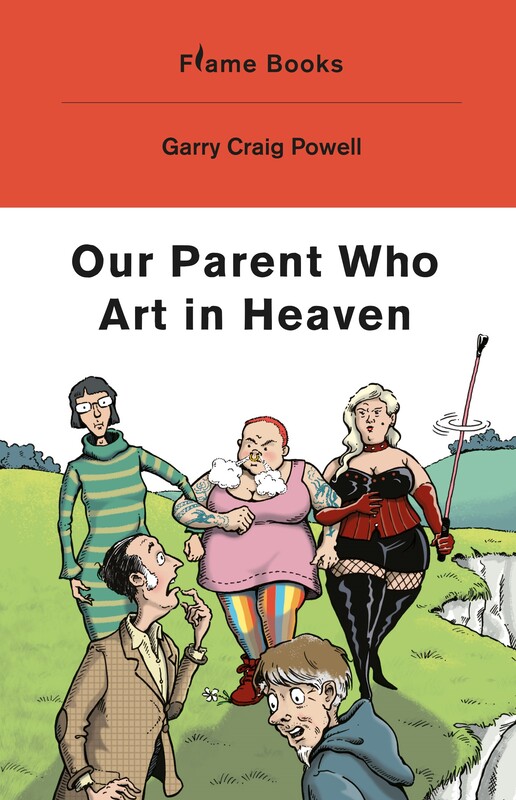

(From my new Substack, Write Dangerously. Subscribe for free at https://writedangerously.substack.com GARRY CRAIG POWELL 29 MAY 2023 ‘Make war on your peers and on yourselves’ said Nietzsche, in The Gay Science. He added, ‘Live dangerously.’ I’m taking that a step further and urging my fellow writers to write dangerously - and artists to paint or sculpt dangerously, and musicians to play dangerously. What do I mean? I take it as axiomatic that most current art, including literary fiction, is rubbish, even the well-crafted stuff. Why? It either kowtows to the current politically correct ideology, which glorifies victimhood, and seeks to destroy the canon, or else harks back to a kind of writing that has become obsolete and irrelevant in the postmodern world. It panders to what Nietzsche called ‘slave morality’ - I argue that in fact wokeness is nothing but Christianity disguised, since it extols the oppressed, and considers anyone who’s been oppressed to be inherently noble. But isn’t this kind? No. It does no favours to the weak, since it teaches them that they are entitled to the fruits of life without having to strive for them - social justice is coming! - nor to the strong, since it seeks to eliminate them. It’s obvious that the whole landscape of the arts has become controlled by a New Elite whose chief aim is to maintain their power and influence by signalling their virtue constantly, and excluding the wicked white men - especially the heterosexual ones - who have been hogging all the attention for so long. If this sounds reactionary, I am not criticising diversity per se. I welcome good writing from anyone of any ethnicity, either sex (sorry, there are only two), or religion or sexual persuasion (provided it’s between consenting adults.) As long as the work is published and promoted on merit. But clearly that’s not what’s happening. Writers and other artists are now feted and marketed mostly because of their bio - their ‘minority background’ and/or because of their woke themes. The result is a cultural catastrophe. Increasingly, novels, short stories, plays and films - all kinds of narrative - are predictable, dull, and uninspiring. The young black woman is invariably brilliant, noble, and strong; the older white bloke is naturally cowardly, stupid, and evil. Who wants to read this hogwash? Only the wokerati, as I call them. And even they only pretend to enjoy it. They read what they are told to read in the Guardian and the New York Times, and by Oprah and the BBC. So this blog or newsletter is an attempt to fight back, to make war, first of all, on my peers who are either too stupid to see the perniciousness of the ideology, or on those who do see it, but who are too cowardly to protest, lest they be cancelled or no-platformed. (I suspect that more writers, agents, and editors are cowards than evil.) Does this make you uncomfortable? Good. I hope to offend. Writing that doesn’t offend anyone is nothing more than bland trash. You might observe that other people are already involved in this fight: Jordan Peterson, Douglas Murray, Joe Rogan, Paul Joseph Watson, and many others. Yes, but not in the world of fiction, as yet. There, as far as I am aware, I am leading the charge! My novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven (Flame Books, 2022) seems to be the first satire on the subject, and David Joiner has dubbed it ‘the anti-woke campus novel of our times.’ Doubtless that is why reviewers have been extraordinarily shy of publishing reviews of it so far - although readers’ reviews have been nearly all positive. I am aware that I may lose friends because of the incendiary tone of what I write. I know too that I am laying my writing career on the line. But I could not live with myself if I did not take up arms in this war. Because this is a war for the soul of man and woman. The globalists want to turn us into neutered trans-human consumers that they can manipulate at will - into slaves, in fact. And they’re succeeding. We have to fight back. Just what am I advocating, then? A return to the realist fiction of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky and Flaubert? Or to the Modernism of Joyce, Musil, and Kafka? No. We can’t go back. We have to create something new and vital, something life-affirming. And that is where the second part of Nietzsche’s dictum comes in. Make war on yourselves. Because we are all - yes, even I, the ‘comandante’ - sometimes fearful, and conformist; we wish to fit in, to be liked, to be admired. We want to be safe. So we submit to being herd animals, slaves. But Zarathustra teaches us the Overman, or Super-Man, who overcomes his weakness. We may not ever attain perfection, but we should be striving for it. We can be strong, like the heroes of ancient Greece, or of Arthurian legend. We can live as aristocrats - aristos means ‘the best’ in Greek, and ‘aristocracy’ means ‘the rule of the best’ and thus is a synonym of ‘meritocracy’. You don’t have to be to the manor born. Like Robin Hood or Sir Francis Drake you prove yourself noble, however humble your background. Shakespeare did so, and Keats, and Dickens. We can too. This blog is a challenge to the creators among you. Dare you think for yourself? Dare you allow the muses to infuse your work, dare you be inspired by myth, by the deepest sources of the spirit and art? Or do you just want to be successful, a rich celebrity? If the latter, then you will do no more than make conformist entertainment. You will remain a slave and your work will be consumed by the other slaves before it’s consigned to oblivion. But for the free spirits, the overmen and overwomen, there is another way: the way of Master Morality. It is dangerous. Follow it, and you will lose some of your friends. You may be reviled. The slaves hate to see a warrior, so they will spit on you and try to destroy you. I know this from experience. They may cry when they hear your work! They are so vulnerable and fragile. And yet, for the true artists among you, this is the only way. We fight or we perish. My vow is that I will not abandon the struggle. Are you with me?

0 Comments

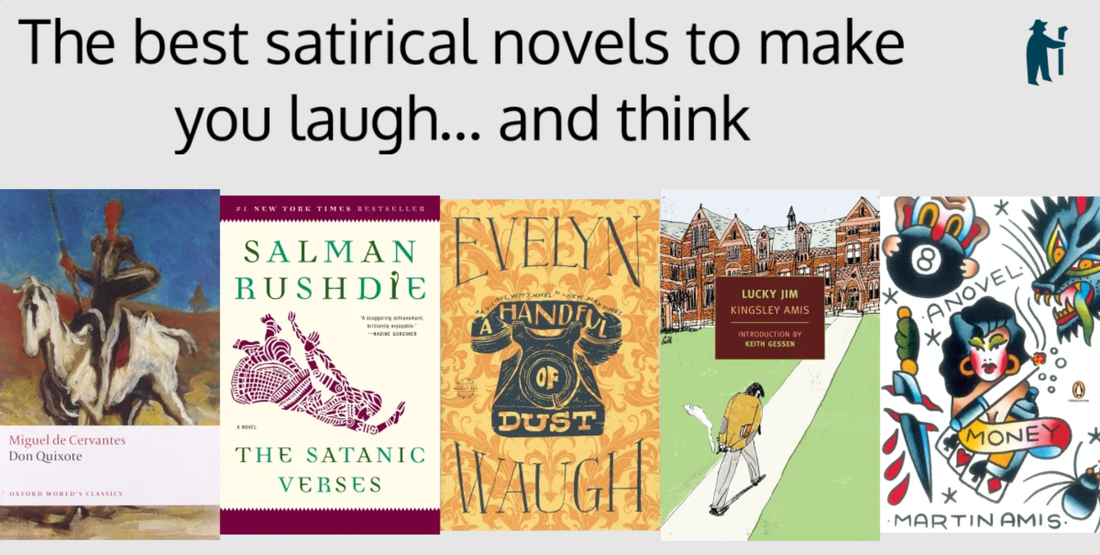

I recently shared my five favorite satirical novels to make you laugh and think on a new website called Shepherd. Shepherd is a new site trying to help readers find books in fun ways. They ask authors like myself to recommend books around a topic, theme, or mood. And, then they remix these book recommendations into categories to help you explore things like satire or identity politics. The list is topical with the inclusion of Sir Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses - and by the way pre-dated the cowardly, evil, and imbecilic attack on the author.

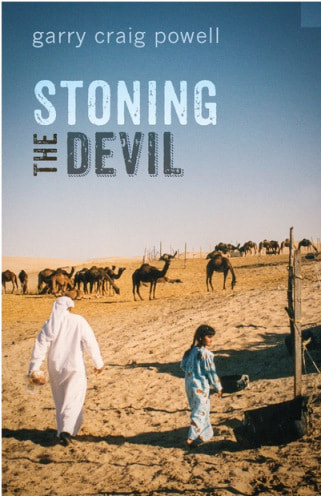

I recently discovered a superb scholarly review of my first book, by a self-described ‘intersectional feminist’. In the abstract to ‘Orientalism and the Failed White Saviour: A Study of Garry Craig Powell’s Stoning the Devil’, (2020)Dr Rathwell writes that my collection of linked stories ‘delivers a critique of Western white expatriate saviourism by presenting a nuanced relationship between his British protagonist Colin, and his Palestinian wife, Fayruz. Through the use of meta-literature, anti-hero tropes and references to violence and sexuality, Powell critiques stereotypical tropes of Orientalism. (…) complicat(ing) them in a literary manner to provide biting criticism of white saviorism in the Middle East. The relationship between Colin and Fayruz therefore serves as a metaphor for relations between the West and the Orient, and in doing so, questions if there can be a post-Orientalist world. Furthermore, the literature is a reflection of the time in which it was created, demonstrating a cultural awareness of the myopic view of Arab women from western eyes, while simultaneously exploring the trope of the failing expatriate.’

I agree with all that. I had read Edward Said’s Orientalism when I wrote the book, if not all the other postcolonial scholars Dr Rathwell references, and the intertextuality was deliberate, as was the metafictional nature of a few of the stories, especially those in which the protagonist is Colin, a professor of colonial and post-colonial literature. The book was intended not as some proselytising feminist or anti-racist screed – I hope my readers are intelligent enough not to need me to preach to them – but certainly as an interrogation of the way westerners interact with Arabs in the Gulf. Still, it’s interesting that the book has been more than once praised by feminist critics. Rathwell herself refers to Paula Mendoza, who wrote an overwhelmingly positive (and astute) review of my book in Lipstick and Politics (Mendoza, 2013). And yet just today I heard that a local artist was angry with me because of my ‘misogyny.’ I wonder where she got the idea that I was misogynist? Has she read Stoning the Devil? I doubt it. Probably she misinterpreted some flippant comment of mine on social media. (A bad habit I need to break!) For the record, as far as I can tell – obviously I’m aware that all men are guilty of subconscious sexism, according to some radical feminists – I am not remotely misogynistic. I absolutely support women’s rights to equality. It’s true that I don’t consider them to be innately superior to men. Nor do I support the kind of exclusion of men (or indeed any other group) being practised by some very privileged women in the media and academia these days. Possibly that makes me a misogynist in the eyes of some – the purblind. But back to ‘Orientalism and the Failed White Saviour.’ I agreed with virtually every word in the article. It’s a brilliant analysis, of its kind. My only criticism of this kind of postmodern criticism is that it concentrates so wholly on the political themes, particularly the themes of identity politics, that it neglects other aspects of the book that I consider equally or more important. Certainly it’s true that the inequality of power between the sexes permeates everything in the book. Nevertheless, it’s also very much a book about failed love, and lust, in a society so corrupted by materialistic values that every relationship becomes a transaction. It’s a study of the essential loneliness of men and women in the early twenty-first century, not only in the Gulf, but anywhere that western materialism has crushed the human spirit and turned men and women into impulsive, self-destructive children who have no self-control, and at times into beasts. That may appear depressing, but it’s also a portrait of people longing for connection, longing for meaning, longing for some kind of spiritual insight, and getting occasional glimpses of it. Rathwell concentrates in her article on the most dysfunctional relationship in the book, and although it’s true that most of the romantic relationships in the stories are no better, there are signs of hope. There’s Tyrone, a remarkably wise, kind Buddhist masseur from Sri Lanka. And while none of the characters is perfect, and most of the Arab women fail to fulfil themselves, there’s a clear indication that one of them, Randa, in spite of her faults, will manage to take control of her life, and live in a satisfying, fulfilling way. And even Colin, for all his repressed racism, is aware of his prejudices, and ashamed of them. He is at least trying to change for the better. In fact, in their own way, almost all the characters are doing their best, perhaps making unwise decisions, but truly trying to live the best way the can, given the circumstances. Isn’t that what most of us do? And wouldn’t it be wonderful if, instead of judging one other all the time, and being outraged by one another, we had the generosity of spirit to see that even the people who disagree with us are doing the best they can, with whatever gifts they have? They have the same longings and needs, as you do, and suffer in the same ways too. This insight is literature’s greatest gift, and if you don’t understand it – if you insist on detesting others because their ideology is different from yours (or skin colour, or sexuality, or sex, or religion, or whatever) then you may as well not read at all. Unless you read merely to confirm your prejudices – which I’m afraid is increasingly the case these days. Everything I write is an invitation to step into the other man’s, or woman’s, shoes. References Mendoza, Paula. ‘Desire and Debasement: Feminism in Garry Craig Powell’s Stoning the Devil.’ Lipstick and Politics. September 8th 2013. Desire And Debasement: Feminism In Garry Craig Powell’s Stoning The Devil – Lipstick & Politics (lipstickandpolitics.com) Accessed January 26, 2022. Powell, Garry Craig. (2012). Stoning the Devil. Cheltenham, UK: Skylight Press. Said, Edward. (1978). Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books. Rathwell, Selena. (2020) ‘Orientalism and the Failed White Saviour: A Study of Garry Craig Powell’s Stoning the Devil’. Siasat Al Insaf – The Middle Eastern Review (1:3) A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius was the very memorable title of Dave Eggers’ 2000 debut, which catapulted him to literary fame. It parodies the hyperbole we are all familiar with from blurbs – especially on the kind of book with lurid, glossy covers that you see on supermarket shelves. It’s witty because it’s ironic – poking fun at the potboilers, while slyly claiming the high ground of literary work. And at the same time, still more slyly, it does after all imply that it's a heartbreaking work of staggering genius itself! It’s a brilliant title, and I believe it was largely responsible for the book’s success. But this post is about genuine blurbs, and the part they play in book promotion.

Not long ago I had a teenage stepdaughter. This year at a book fair in northern Portugal, where I live, I gave her the money to buy a book of her choice. She selected The Da Vinci Code. As you might imagine, I groaned, not only inwardly either, and suggested she look for something else, but she was adamant. I asked her what had attracted her to the book. Had she read even the first page? She had not. But she liked the cover, and the blurbs claimed it was brilliant. I tell this story not to have fun at the expense of a fourteen-year-old, but to point out how most readers probably choose their books – including more sophisticated ones. How many of us are not seduced by a fulsome blurb by a celebrated author we know and respect? And it’s not only potential readers who might be swayed by the blurb. At the moment my publisher, Flame Books, wa new press, is negotiating with book distributors in the UK. Apart from the massive commission you pay them, which might just influence them a bit, what determines whether they will distribute a book, and what whether bookshop managers will display it? Clearly they aren’t reading every book submitted to them from cover to cover. I suspect they glance at the cover, decide whether it looks professional and eye-catching, and read the publisher’s blurbs and recommendations by the famous. At least I hope they pay that much attention to an unknown book! The anxiety that nags at the author is that they will only distribute and display books published by the Big Five. That would be a pity, because the Big Five have become conservative and predictable, and are serving up formula books, just as Hollywood produces formula movies, with rare exceptions. Whatever else you may think of it, my novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, is quite unlike anything being published today, so it deserves an audience, whether it’s in tune with the zeitgeist or not. And here are some of the blurbs I’ve got, which I set before you (ahem!) not in the spirit of self-promotion, or only a tiny bit, but to illustrate what a good blurb should do: give an idea of the flavour of the book, compare it to known novels, and incite your curiosity so that you want to know more. I’d love to hear whether in your view they succeed. ‘Pure comical genius. Spot-on (uproarious) observations about today’s imbecile cancel culture. You’ll be reading parts of this book to friends and strangers alike – if you can stop laughing long enough. Powell brilliantly hoists woke insanity with its own petard.’ – Gary Buslik, author of A Rotten Person Travels the Caribbean ‘When I started reading Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, I laughed so loud I scared myself – when I finished it, I realised I’d just read a brilliant book. If I taught English Lit, I’d put Powell’s satire on my syllabus with writers such as Evelyn Waugh, DH Lawrence, and John Fowles.’ – Kirsten Koza, humourist, author of Lost in Moscow ‘In Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, Powell has penned what may be the anti-woke campus novel of our times, a rollicking satire equal to the wittiest and most keenly observed of Tom Sharpe and Evelyn Waugh.’ – David Joiner, author of Kanazawa What do you think? Two comparisons to Evelyn Waugh, one of my great literary heroes! I’ll take it! They all find it funny, and see a deeper, more serious side to it too. As for the ‘masterpiece’ of the title – that’s Gary Buslik talking about the novel again. I don’t care whether the book makes me any money or not, or whether it makes me famous or infamous – Kirsten Koza anticipates the Twitter mobs coming for me with pitchforks, screaming for the novel to be cancelled – as long as people read it. I don’t claim to be a latter-day Giordano Bruno, but I stand by what I say and accept the consequences. Fiat lux! Garry Craig Powell’s debut novel Our Parent Who Art in Heaven will be published by Flame Books in the United Kingdom on April 15, 2022. |

Garry Craig Powell'sdebut novel, Our Parent Who Art in Heaven, was published by Flame Books in the UK on April 15, 2022. Archives

June 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed